In 1920, American Prohibition went into effect, reaching out to take the entire nation in its grip. And the moment it did, an entirely new drinking culture reared its head—a culture which, could the teetotalers have foreseen it, might very well have sent the temperance crusade veering off its tracks long before the 18th Amendment was penned.

In the intervening years, the nation flouted Prohibition, demonized it, repealed it, forgot it, remembered it and romanticized it. But what was the era like in the upper left corner of the country?

The Northwest’s experience with Prohibition was far different from that of cities made most infamous by it. Those cities, moonshine-soaked and mob-ridden, fomented some of the most sensational clashes and scandals we associate with Prohibition today. Neither moonshine nor mobsters reigned in the Northwest. Instead, the region had its own set of stories that gripped the nation. It had more, better and easier booze than any other region in the United States. It also had what was arguably the most sophisticated, successfully operated liquor bootlegging operation the nation has ever seen. By any measure, the Northwest’s incomparable Prohibition history is one worth remembering.

The Evergreen Playground

Prohibition wasn’t conjured from thin air. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, booze was perceived as lubricating a mélange of serious social issues—vice, violence, ubiquitous drunkenness and sluggish industry among them. It wasn’t just a few axe-brandishing teetotalers who were concerned, either—Prohibition-related elections set voter turnout records, some of them as of yet unbroken, and alcohol regulation legislation had been successful as early as 1844, when Oregon passed the nation’s first temperance law. On Jan. 1, 1916, Oregon, Washington and Idaho, along with four others, became the first of 23 pre-national Prohibition dry states in the nation. Others followed like dominoes, and the momentum would send the United States barreling headlong into nationwide Prohibition four years later.

By that time, the Northwest was poised to become a bootlegger’s paradise. Statewide prohibitions had, in effect, provided a low-stakes practice round for smugglers. Meanwhile, British Columbia had just spearheaded a renunciation of Canada’s own national prohibition, and was perfectly positioned to serve as the American Northwest’s liquor cabinet.

To top it all, the Northwest’s innumerable islands and hundreds of miles of coastline could not have been devised more strategically for smuggling. And even without these challenges, the 20th U.S. Prohibition District—encompassing Oregon, Washington and Alaska—was allotted a fraction of the already inadequate $2 million national enforcement budget, plus a lonely pair of Coast Guard vessels to patrol its jagged coast. The New York Times would remark over and again in the next 13 years that the 20th District was the most difficult district to patrol in the nation.

Thus, the Northwest provided the most opportune possible place for bootlegging alcohol (also referred to as rumrunning) in the United States—it just took someone to spot the opportunity. And as chance would have it, someone did.

The King of Northwest Bootleggers

The man was Roy Olmstead, and he would become one of the most famous and revered rumrunning kingpins in the country. At the time, though, he was the youngest, brightest lieutenant in the Seattle Police Department. Talented, charismatic and universally well liked, Olmstead was also bright enough to see that Seattle’s rumrunning networks were in complete disarray. With a businessman’s pragmatism and law enforcement’s inside information, he quickly took on the considerable task of keeping liquor in Seattle.

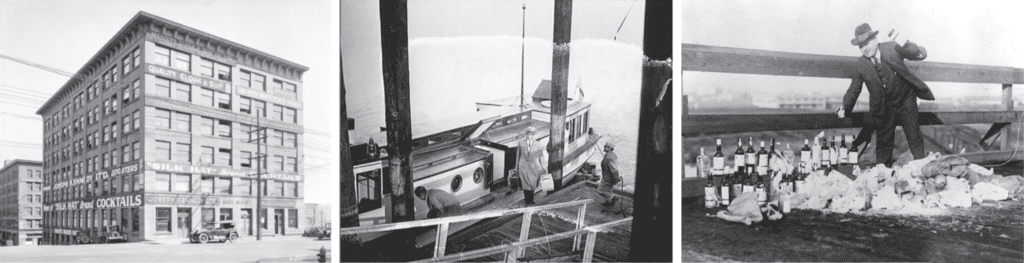

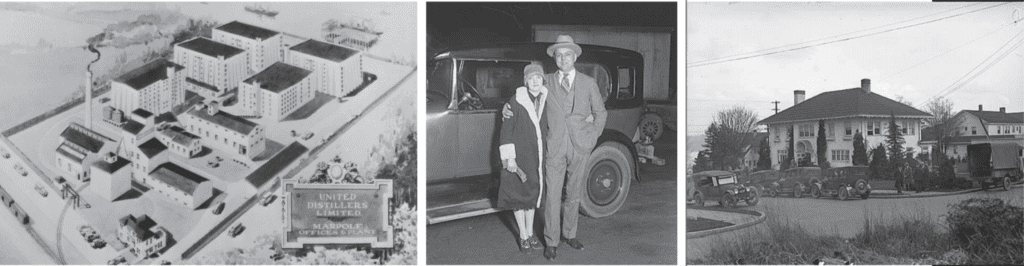

On March 22, 1920, Olmstead had already been arrested in connection with the largest seizure of liquor recorded in Puget Sound. Dismissed from the police force and newly unfettered, he began purchasing Canadian liquor on an unprecedented scale, using ships cleared for Mexico to avoid Canada’s U.S.-bound liquor tax. Caching liquor in places like D’Arcy Island, a widely avoided leper colony in the San Juans, Olmstead would wait for inclement weather before sending his smallest, quickest boats to retrieve it. In a matter of months, Olmstead controlled virtually all of the liquor coming into the Pacific Northwest’s coastal cities, and had extended his network south, reaching all the way to California.

At his peak, he was unloading more than 200 cases per day in Seattle alone, often in broad daylight downtown. Olmstead reportedly was Seattle’s biggest single employer (employing a workforce at least three times the size of the federal unit responsible for enforcing Prohibition in the area), and was grossing more than $200,000 a month in liquor sales. With his wife Elise (known as Elsie), Olmstead purchased a beautiful colonial mansion at 3757 South Ridgeway Place, as well as one of the city’s first major radio stations, KFQX. Every night at 7:15p.m., Elsie would read bedtime stories over the radio to the children of Seattle (rumors that the stories contained coded messages for Roy’s rumrunners were unfounded). Today, the mansion still stands at its original address looking much as it did during the 1920s, while the radio station moved out and morphed to become KOMO.

In the Queen City, Roy Olmstead was recognized and lauded as anything but a criminal. Rather, he was the Robin Hood of Northwest hooch, and perhaps the city’s best-respected public figure. His morals were steadfast: he never watered his booze down a drop, never trafficked in narcotics and forbade his employees to carry guns. Within Olmstead’s sphere of influence, rumrunning was understood to be a “respectable crime,” and Seattle’s most prominent citizens were proud to name him among their friends.

Romance & Realities of the 1920s

As much of the rest of the country dealt with turf wars and shootouts, a rare spirit of cooperation and responsibility characterized the Northwest rumrunning industry even beyond Olmstead. According to author Stephen T. Moore in his book “Bootleggers and Borders: The Paradox of Prohibition on a Canada-U.S. Borderland,” nearly 100 regional bootleggers convened at a Seattle hotel in 1922 to swear off the narcotics traffic, set fair prices, enumerate a code of ethics and delineate “approved business methods.” Violence certainly existed—there are true Northwest tales of a bold jailbreak, liquor heist and car chase near Newport, Oregon; of hijackers’ gunfights on the Puget Sound; and of a cold-blooded international murder case that captivated the United States and Canada alike.

Meanwhile, corruption ran rampant among legislators and law enforcers: Portland’s mayor, George Baker, ordered the Rose City’s confiscated liquor special-delivered to his home by vice squad members. Nearly half of the Seattle police force and Dry Squad were known to be on the take. Speakeasies in one form or another laced the cities, found in private homes, restaurants, hotels, soda fountains and pretty much any other place inspiration struck. And perhaps the harshest reality of Prohibition was the abuse of governmental power and encroachment on civil liberties in the name of enforcement. This national tension finally came to a head in Seattle, in the biggest liquor smuggling case ever tried under the 18th Amendment. Again, Olmstead was at the heart of it.

Desperate to staunch the unending flow of liquor, 20th District agents Roy Lyle and William Whitney had resorted to wiretapping, expressly forbidden by United States constitutional law, to finally arrest Olmstead in his Mount Baker mansion—and, unthinkably, the judge in question admitted the illegally obtained evidence. Olmstead v. The United States was appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, where the illegally informed verdict was upheld in a 5-4 decision. Nevertheless, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis paved the way for future right to privacy legislation with a withering dissent.

Olmstead simply laughed at the verdict, and with an “I’m not complaining—I broke the law,” he would spend his next four years in the federal penitentiary on McNeil Island, where many bootleggers were detained. But the “Whispering Wires” case, which had ensnared national attention and front-page headlines, rang a harsh chord with the public thanks to widespread respect for Olmstead and distaste for the level of federal intrusion the wiretapping came to symbolize. The case precipitated the dismissal of the pair and their team by 1930, and is recognized as having been a major impetus for repeal. Olmstead never trafficked in liquor again and dedicated himself in his later years to helping rehabilitate the inmates of McNeil Island. He was granted a full presidential pardon by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, two years after Roosevelt signed the official proclamation annulling Prohibition.

Present-Day Reverberations

The ratification of the 21st Amendment on Dec. 5, 1933, repealed the 18th Amendment and ended Prohibition, but the movement’s effects continue to not only shape our present-day beverage culture and industries, but also capture our collective imagination. Government regulations, imposed directly after repeal, have loosened only very slowly over the decades, and institutions such as the Oregon Liquor Control Commission are still in place today evidencing the long-term effects of the temperance movement. At the same time, neo-speakeasy bars, the renaissance of classic cocktails and a recent grassroots movement to celebrate Repeal Day as a national holiday are all evidence of a recollection and romanticization of the time period.

Beyond those more concrete effects, though, what’s truly remarkable about the Northwest’s unique Prohibition legacy is that the same spirit of cooperation and dedication to quality persists today in our regional beverage industry—and, arguably, so does a taste for the best booze to be had in the country. Here’s to the predecessors who paved the way.

Story featured in the 2015 Spring issue of Sip Magazine.